Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

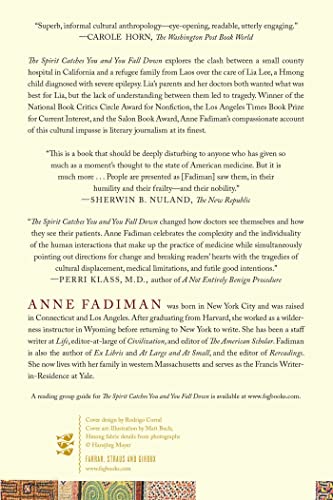

Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down : Fadiman, Anne: desertcart.in: Books Review: Good - Good Review: Higly recommended book. - Anne Fadiman's work should be seen as a classic in medical anthropology. Higly recommended book.

| ASIN | 0374533407 |

| Best Sellers Rank | #232,971 in Books ( See Top 100 in Books ) #291 in Cultural & Ethnic Studies #740 in History of Civilization & Culture #782 in Ancient History (Books) |

| Customer Reviews | 4.6 4.6 out of 5 stars (5,544) |

| Dimensions | 14.02 x 2.4 x 21.03 cm |

| ISBN-10 | 9780374533403 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0374533403 |

| Item Weight | 308 g |

| Language | English |

| Net Quantity | 310.00 Grams |

| Paperback | 368 pages |

| Publisher | Farrar, Straus and Giroux (24 April 2012); Macmillan Publishers Ireland Limited; Product Safety Contact; [email protected] |

A**R

Good

Good

A**R

Higly recommended book.

Anne Fadiman's work should be seen as a classic in medical anthropology. Higly recommended book.

J**A

Five Stars

Brilliant Book

C**K

By the time more than two hundred people have reviewed a book and a hundred and seventy people have given it five stars, adding one's own two cents to the mix seems almost beside the point. Yet the significant minority who have written highly negative reviews seem to call out for response. Besides, I happened to love the book and want simply to share that fact. I knew nothing about the Hmong before reading this book and, from it, learned a lot about their history and traditional culture. I don't think there is any need to fear that readers of this book will imagine all Hmong to be like the ones Fadiman depicts, any more than, if I wrote a book about my Sicilian-immigrant great-grandparents (who probably had more in common with Fadiman's subjects than one might at first suspect) people would think it revealed much about Italian-Americans, or Italians in Italy, today. This book is "woven" out of two main strands: alternate chapters tell the story of the family whose daughter has major epilepsy, and alternate chapters describe the history and culture of the Hmong. Each strand is brilliantly done and as the book progresses each sheds light on the other. But there is a class of readers to whom I would recommend this book even if they have no interest in the Hmong, and that is anyone who cares about medicine in general and the state of health care in today's America in particular. I am an articulate, educated native speaker of English and I've had frustrating experiences. When I was seven I was in hospital with severe asthma. I was alone in the room when a nurse came in with what I now know was an intravenous bag, on its large metal rack, with tubes and needles dangling from it. I had never seen IV before and had no idea what this was. I asked the nurse; she said she was going to give me a blood test. She inserted the needle into my arm, wrapped a bandage around it, and walked out of the room. This terrified me: I knew very well that a blood test involves inserting a needle for about one minute. Why did the woman lie? Too busy? Too arrogant or stupid? I am fortunate today to have an excellent doctor but in the past I've had no shortage of this sort of "just obey and don't ask questions" attitude. Now imagine that I am a relatively uneducated American and I'm in a village in Laos with my child, who suddenly becomes gravely ill. I don't understand a word anyone is saying, but they're bringing my child some strange boiling liquid. Do I pull my child away, refusing to let other people do potentially harmful stuff to her? Or do I trust them because there's at least a chance that it might help her, and doing nothing is the greatest risk at all? But here is what Mrs. Fadiman's book shockingly reveals: the American doctors were sometimes more wrong than the girl's parents were. At least one of the medicines which her parents refused to give her really did turn out to be harmful to her. When the parents had custody of her and took care of her in their own way she flourished--who knows whether she would still be well now if they had been able to keep her? Mrs. Fadiman interviews the various doctors extensively. Most of them emerge as fiercely intelligent, thoughtful people who are examining their own mistakes. One of them points out the harmful assumptions behind a lot of the language used--"compliance", for example. It reduces the patient to a child, or the subject of a tyranny, from whom nothing is expected but obedience. Finally, this book asks us to ponder a difficult political problem. How much freedom should parents have over the raising of their own children? The parents in this book had their child taken away because they were not giving her the medicines prescribed by the doctors. Was this just? It seems to me that the government, in this case, did either too little or too much. If they had taken the child away for good, then perhaps, with consistent application of the prescribed medicines, she would have done well. If they had left her with the parents entirely, then she still might have done well (remember the parents are demonstrated to have been right more than once about their daughter's health on occasions when the doctors were wrong) and at least the parent-child bond would not have been violated as horribly as it in fact was. But the shuttling of the little girl back and forth between her parents and other families was inexcusable. All in all, a thought-provoking, balanced, and humane book, worth reading by anyone who cares about health, culture, family, folklore, and the human condition. And by the way, I despise political correctness and although I am living a genuinely "multi-cultural" life, most trendy talk about 'multi-culturalism' makes me run in the opposite direction. This book is a model of how to talk about the clash between two cultures in a way that is neither condescending (on either side) nor superficial or politically-loaded.

M**Z

Aún no lo he terminado, pero me gusta mucho la historia y cómo escribe la autora.

L**N

Well-written and intriguing the way the author weaves the family story with the recent history of the Hmong people and a description of their culture. I was very touched by the stubborn way they adher to their values and customs and especially by the depth and commitment of their love and. Ari g for each other. An important counter model to our own very individualistic society.

N**Y

The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down absolutely wrecked me—in the best way possible. It’s the true story of a Hmong family in California whose daughter, Lia, has epilepsy, and how everything goes sideways when their cultural beliefs clash with the American healthcare system. As someone who works in healthcare, I found this book incredibly powerful and frustrating and eye-opening all at once. It’s not preachy or dry; it reads like a story, but hits like a case study in how good intentions can still lead to heartbreaking results when people just don’t understand each other. Anne Fadiman does an amazing job of showing every side with compassion—there’s no clear villain here, just people doing what they believe is right, and a system that wasn’t built to bridge the gap. Honestly, I think this should be required reading for anyone working in medicine, social services, or education. 📝 Would love to see more books like this featured on Amazon. Honest, powerful stories that need to be heard. (And hey Amazon, I’d gladly review more of them—just saying. 😉)

W**N

When a doctor sees a patient for a consultation, it is easy to assume that everyone wants the same thing. The patient wants help with their ailments. The doctor wants to provide that help. But sometimes things can get in the way. We have all experienced it to some degree. Perhaps the patient wants a kind of help that the doctor believes is not appropriate. But what about the opposite scenario? What if the doctor wants to give treatment, but the patient refuses? What if the patient in question is a child, and the parents are the ones refusing? This book, researched over 8 years, takes a massively in-depth look at this problem, crystallised in the relationship between a family of Vietnamese Hmong immigrants in California, and their doctors, when one of their daughters develops life-threatening epilepsy. The doctor-patient relationship is massively challenging. The family don’t speak English, but even once the language barrier is overcome (to an extent) with interpreters, they have unrealistic expectations from the American medical system, and a completely different set of beliefs about illness. The doctors believe epilepsy is a pathological process in the brain, while the family believe “the spirit catches you and you fall down”. Aside from the medical parts, which are described carefully and objectively, and without portioning any blame, this book is a very touching story of a family coping with adversity in a brave and dignified way, as well as a simple history of the Hmong people of Vietnam, covering some of their early history, their legends, their beliefs, their tragic involvement in the Vietnam war, and their forced immigration. The three tales are woven into a coherent narrative. There is certainly an element of drama in Lia’s repeated admissions to hospital, prolonged seizures and brushes with disaster. The odds are stacked up against Lia, her family and her doctors, all of whom have the child’s interest firmly at heart. Some of the doctor-patient interactions are terrifying. For the first few visits to the emergency room, the doctors and the family have no means of communication whatsoever. Since the seizures had generally finished by the time Lia reached hospital, the entire reason for her visit to hospital was missed. It was only after being sent home several times that she arrived at hospital still having a seizure and the doctors realised she had epilepsy. Later, despite complex treatment regimes, Lia would repeatedly turn up at hospital with no anti-epileptic medication in her bloodstream. Her parents believed the drugs were not working, or even made Lia worse; this may have been true, or it may not have been, and none of the protagonists could really be sure. The book skates carefully through some of the dilemma’s faced by the officials trying to care for Lia – the doctors, nurses, social workers, lawyers and translators. At one stage, Lia is forcibly removed from her loving family and placed in foster care, a decision which is easy to understand but hard to justify knowing the full facts. The end of the book revolves around a particularly severe episode. Could this story have had a different ending? The events of the book occurred in the 1980s – how would this play out 30 years later? Maybe the ending would be no different – medicine does not have all the answers. But some things have changed for the better. Researchers have studied compliance (now correctly called “adherence”). Doctors are less paternalistic, more open to allowing alternative “healers” to be involved, and there would hopefully now be more dialogue around treatment decisions. Translators are more widely available, either in person or by phone, and modern doctors would hopefully find it easier to communicate with Lia’s family. Hopefully they would also make more of an effort than featured in some of Lia’s early encounters with doctors. But failures like this still occur today. This book is far more than just a case history. I defy anyone to read this without caring about Lia, her indomitable parents, and even her doctors, who tried their hardest to fight for her and her family when others might have given up. Attitudes and standards have changes in the 30 years that have passed, and this book was one of the catalysts for change. It is compulsory reading in some medical schools, and I think all doctors should read it.

Trustpilot

1 month ago

1 month ago